Naturalizing the East-West Divide Online/ A Fragment of the Iron Curtain Mapped through Deaths.

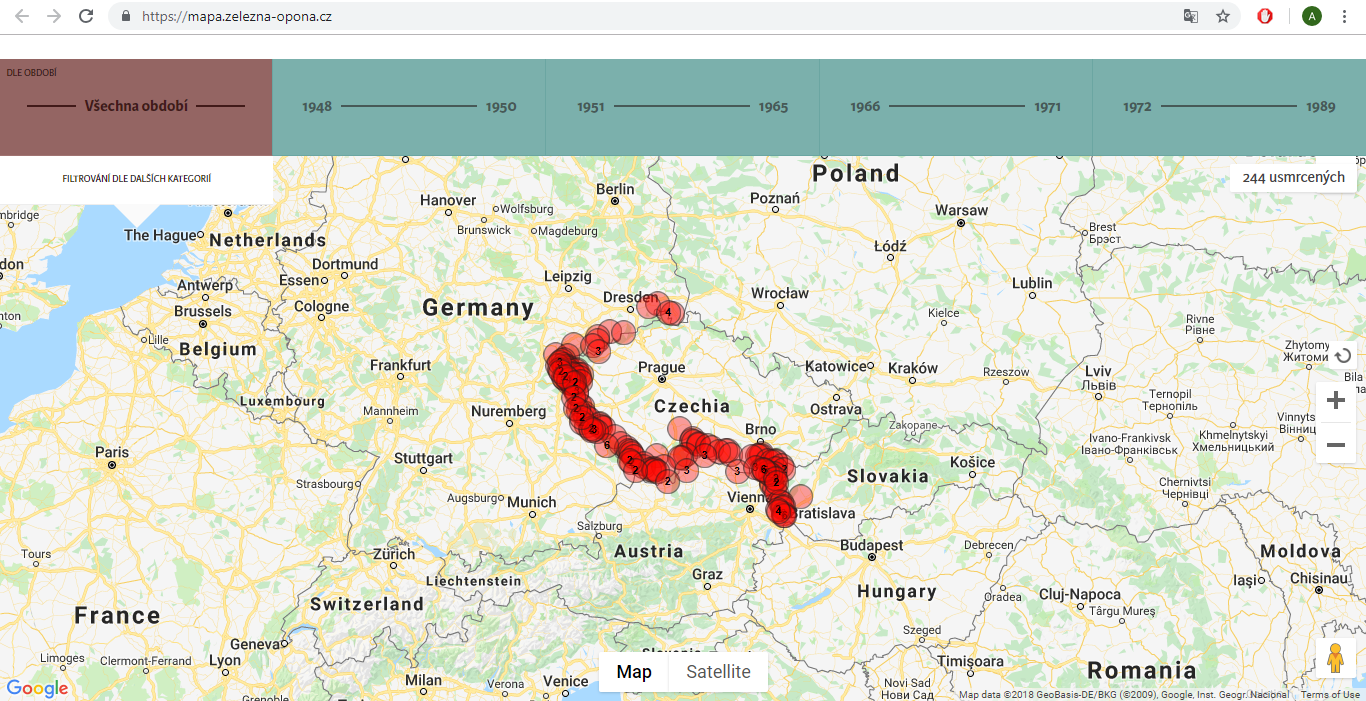

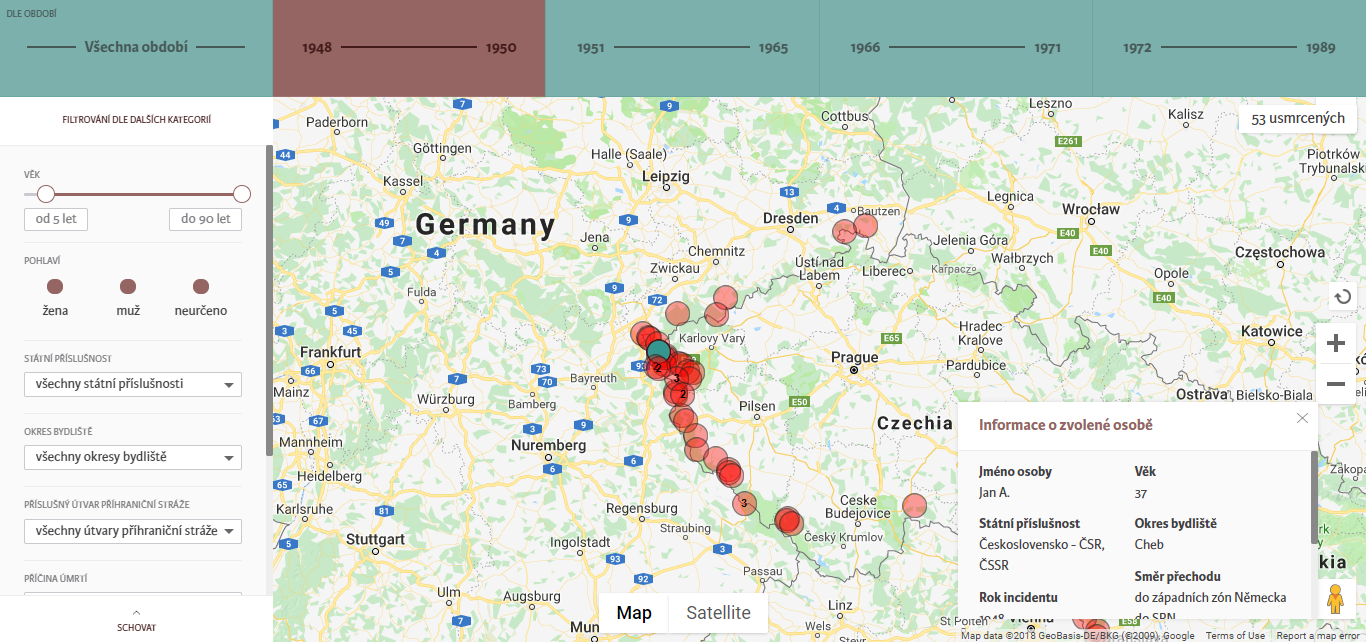

East-West: a familiar dividing logic. In the context of Europe, a separation along this line was a material, violent, reality throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Almost three decades after the fall of the boundary that Churchill termed the Iron Curtain, this division continues to perform difference. Recently, I encountered a segment of this line in a web application. This web-app, entitled Map of the Iron Curtain (Mapa.zelezna-opona.cz, 2015), serves as a visualization of the outcome of a research project about deaths on the Czechoslovak border conducted by the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes (ISTR). The figure below shows an image of the interface; the red circles mark the locations where individuals were killed between 1948 and 1989.

This visual probe is the primary point of departure for my exploration in this essay. The bold red marks construct a wall in the familiar digital grounds of GoogleMaps. This wall is a segment; instead of encircling an inside space, it distinguishes two sides inconclusively. I would like to suggest that in mapping the division between Eastern and Western Europe through deaths, the web-app reinforces the logic that underlies it. Through this essay, I therefore speculate about the ways in which borders naturalize the dividing logic between East and West. I use the concept of naturalization as an analytical tool; drawing on Bal’s (2002) ideas on using the concept as a method, I confront my case with the notion of naturalization, letting the concept to be shaped in the process. This is also the reason why I prefer to avoid sketching out rigid working definitions. The only reference I wish to bring in is to Law’s (2015) engagement with the concept which frames it in the context of the nature/culture divide as a term that implies a single reality – one true external order. Naturalization can therefore be seen as tightly-knit with our ontology.

This essay is written in points; I leave it for the reader to draw a line through them. Loosely speaking though, I first attend to the web-app itself drawing on the archival material and research project behind it. Next, I bring in literature to engage with boundaries on a theoretical level. Finally, I situate the discussion in the European context through two studies that likewise reflect on borders.

Transforming the physical into digital

I begin my exploration by looking into the process through which the web-app was created. This process is one of transition; the digital visualization is constructed from a selection of physical material, it is a remediation that reframes the original documentation that it draws on. The app is a frontend encounter with the research project intended for academics and the wider public. Much work and research, however, is behind this touch point, parts of which I would like to discuss here in order to foreground some of the decisions made in the creation of the visualization.

In 2009, the ISTR launched a project aimed at compiling a comprehensive overview of information about the people who died at the border during the Soviet regime in Czechoslovakia, in the period 1948-1989. To this end the ISTR conducted research drawing on available archival material. This research resulted in a publication entitled The Iron Curtain in Czechoslovakia (Mašková & Ripka, 2015), which is accompanied by an online application that serves as a visualization of the deaths studied in the research. In order to ‘provide as many facts as possible about the true interventions of the border guard’ (Ustrcr.cz, n.d.),1 the researchers compared archival documents of the Border Guard unit2 and of the State Security.3 The study also made use of files that were complied and used in legal investigations of the deaths after 1989 by the Organ for the Documentation and Investigation of Communist Crimes.4 Next to this, the project built on earlier archival research conducted by Pulec (2006), which published a list of people killed at the borders; this list served as the pre-selection of cases that the ISTR project focused on.

The web-application assumes a narrow focus on the deaths of those trying to cross the border. The research project in itself however, aims to answer a broad range of questions that relate to the Western border of the Soviet bloc more generally.5 It is for instance concerned with the issue of what life was like in the Czechoslovak border zone, which was generally two to six, but in some places up to twelve kilometers wide. It attends to details, such as that all churches were torn down in the border zone (Mašková & Ripka, 2015). It retraces the bureaucracy through which travelers needed to go through before being permitted to cross the frontier across onto the territory of Western neighbours. This general context then serves as an entry point for discussions about the deaths that occurred in this zone. In the web-app, the focus is directed from the deaths outward. Contextual information about the border zone is not provided, rather, (minimal) information about it can be extracted from the elaborations on the individual deaths. These therefore come to channel the narrative and constitute the border zone between 1948 and 1989.

The deaths presented form a selection. The project thus far visualizes and documents 266 deaths, the same cases that it also made use of for statistical analysis. These 266 individuals constitute a selection from Pulec’s (2006) list6 of those who died at the border. The selection includes all individuals whose intention of crossing the border could not be disproved; this means that it includes people who aimed to cross the border as well as 17 people whose intentions were ambiguous. What is relevant to mention is that the project excludes deaths of the border guards themselves, which numbered somewhere between 400 and 600 (Mašková & Ripka, 2015). The framing of what constituted ‘being killed at the border’ is therefore restricted to having the intention of crossing it – death at the border while in uniform is disregarded, even though it was the more common scenario.

The project splits the 1948-1989 period into four separate periods. While this periodization was initially intended for grouping the available data into relatively homogenous sets as to facilitate statistical analysis, it now also structures a viewer’s experience of the web-app. The research stresses that these do not match up with the periods into which the Soviet regime is typically split into from a political perspective. The division of time into these periods (1948–1950, 1951–1965, 1966–1971 and 1972–1989) is prominent in the application, as filters with the given ranges of years regulating the deaths that are mapped line the top of the webpage. This custom periodization at once illustrates a chronology in the ongoing phenomenon of killings at the border and communicates some of the key changes in legislation that concerned the borders. In 1951, for instance, the Border Guard unit was created. In 1966, it was transferred under the administration of the Ministry for National Defense and, simultaneously, the high voltage barriers present in the border zone were depowered. Between 1972 and the fall of the Soviet regime, the Border Guard was under the executive control of the Federal Ministry of Internal Affairs (Mašková & Ripka, 2015). These custom temporal categories of the border region generate a unique historical timeline of the zone that is relative to its own developments – they create the border’s own time-space.

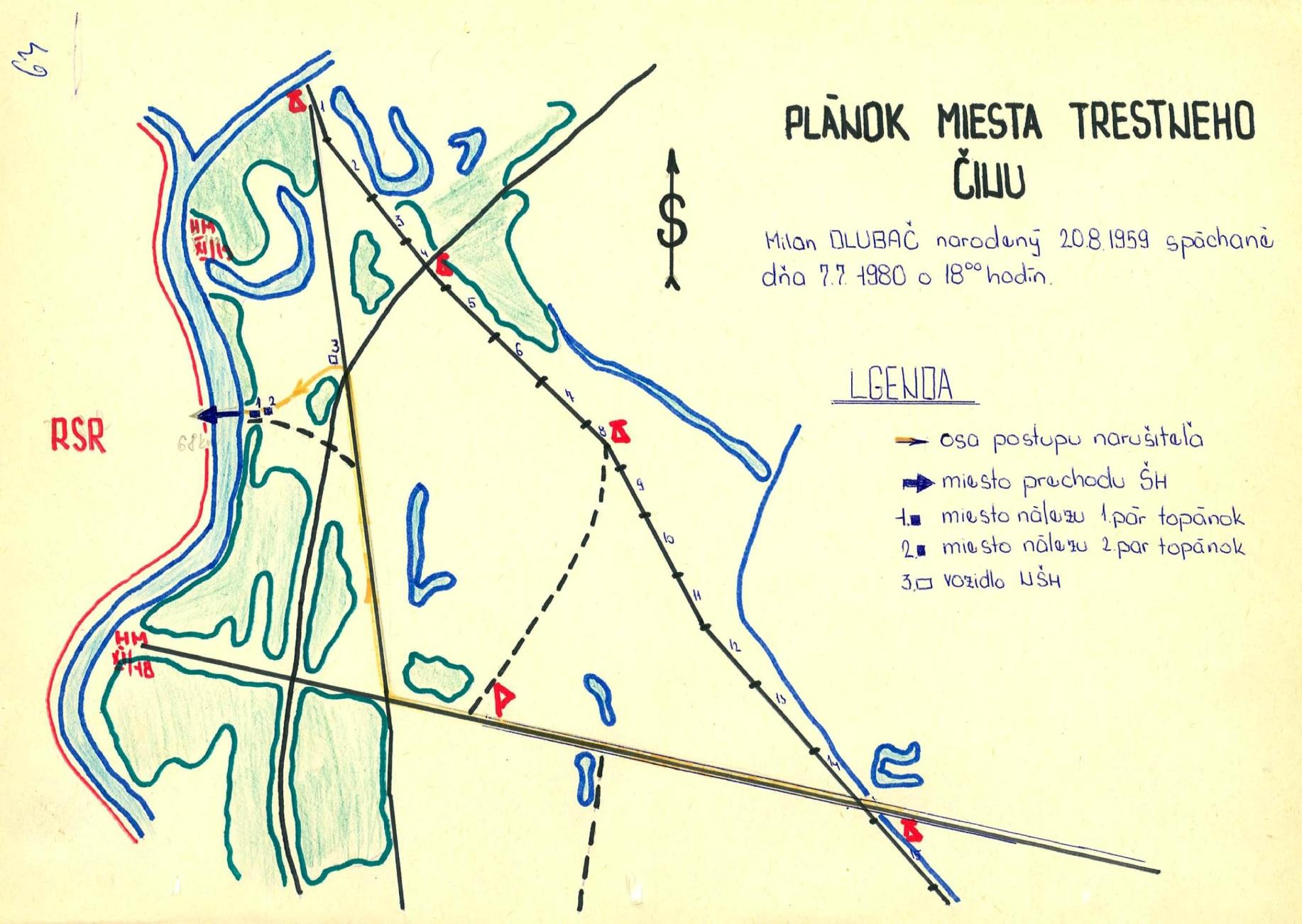

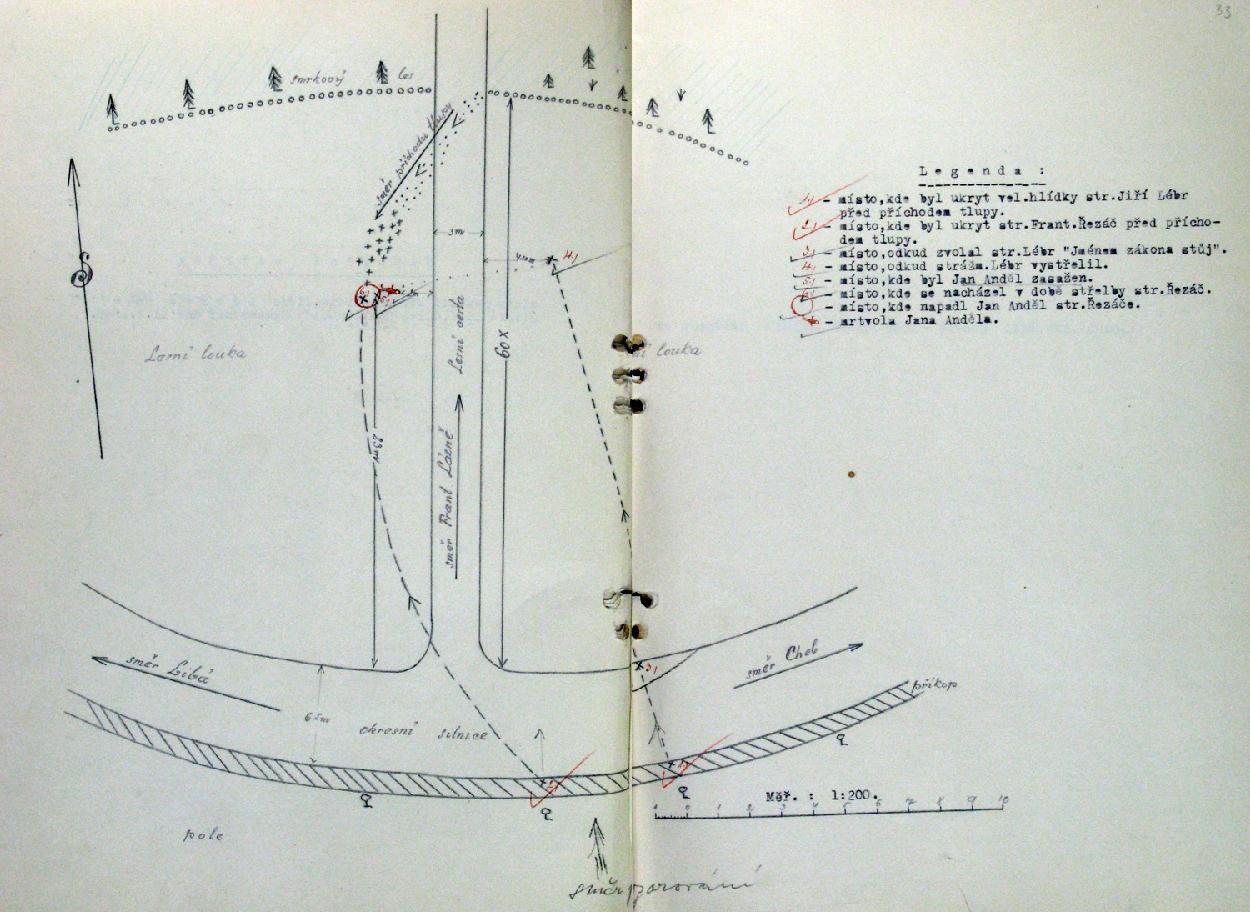

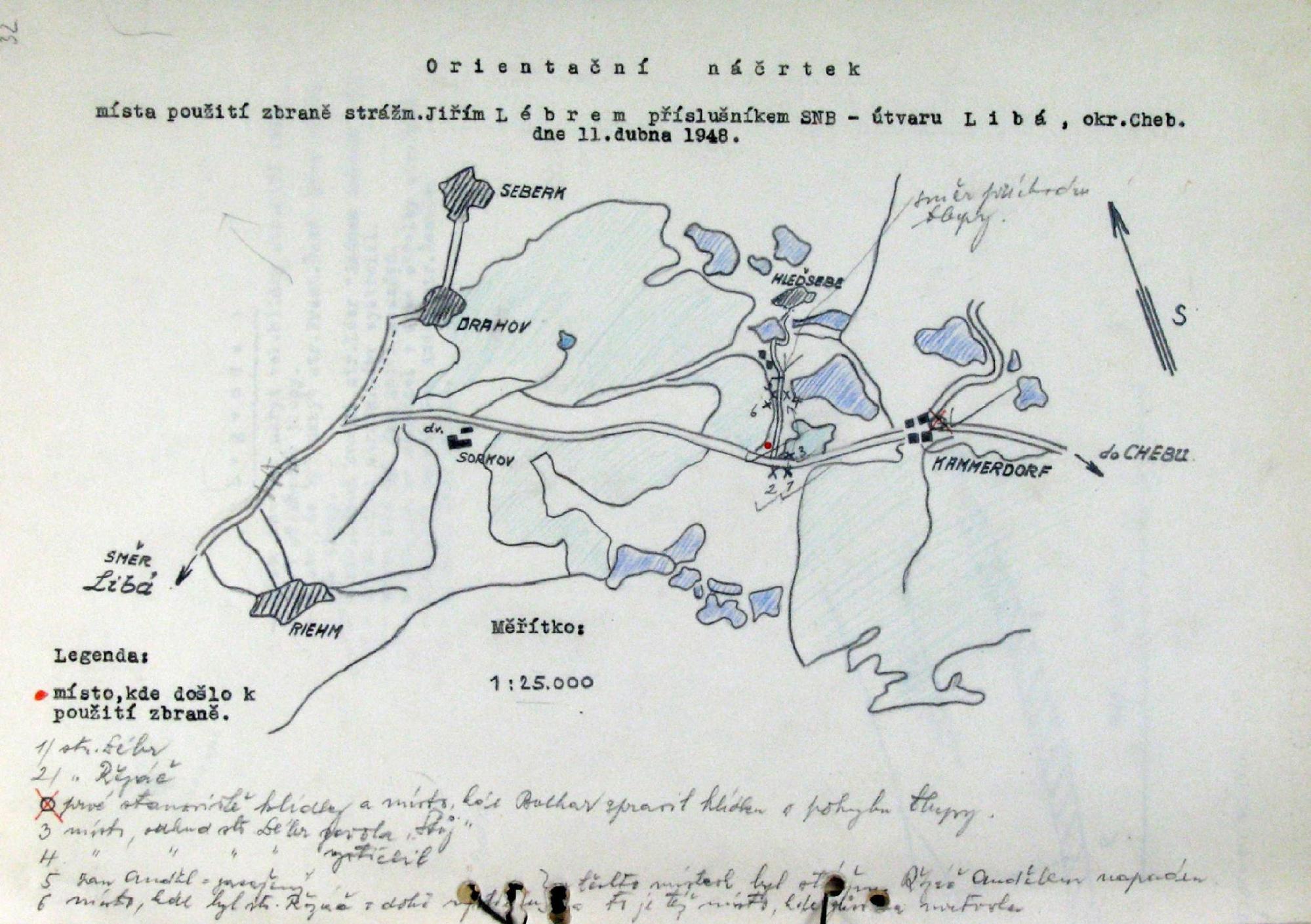

The sketches originally produced by members of governmental bodies like the Border Guard or National Security Corps are not primarily focused on documenting death or mapping the border. The sketches in figures 2 and 4 map the circumstances of a ‘criminal offence’ of the individual crossing the border and ‘weapon usage’ by the border guards respectively. In some cases, locations of death are not mapped, such as in Brejka’s case (figure 2). In other cases, like Anděl’s (figure 4), bodies of those killed in the incident are marked in the diagrams (often with an x), but many other objects and events are symbolized with an undifferentiated importance. Figure 2 shows places where shoes were found, vehicles were stationed and routes taken. In Figure 4, the hiding locations of the two border guards involved in the incident as well as the location from which one of them ordered Jan Anděl to “Stop in the name of the law” are recorded on the map. Comparing the location sketched across several different cases reveals that they differ from one another in both style and content. This makes it difficult to use the physical archival material to arrive at a clear-cut overview of the deaths on the borders. Next to this, when compared to the way the deaths are presented in the web-app, the contextual information obscures the focus on the death of the individuals killed.

The web-app transforms the locations of the deaths from the personal hand-drawn physical sketches of border guards that are kept in an archive to the open and public space of Google Maps. Unlike the archival sketch that may be cumbersome, difficult, or at times impossible to access, the by now familiar landscape of Google Maps is accessible to a wide audience; both in terms of its access and accessibility. Figures 3 to 6 below give an impression of the ways in which the representations of the deaths at the Czechoslovak border have been transformed through the creation of the ISTR web-app. To name a few points of comparison, the use of the GoogleMaps API in the web-app results in an aesthetic and environment that are both likely familiar to the audience. The web-app can display all the deaths simultaneously with the possibility of zooming in or out of the image. The red circles marking the locations of the deaths thereby line the Western border of the online representation of today’s Czechia and Slovakia as a consistent thick stretch. The individual archival documents on the other hand, form distinct entities that are fixed to a single scale. The paper copies cannot easily be combined to form an overview of the aggregated deaths in the border zone, nor are they often represented as points along a border.

Connect the Dots… Naturalizing borders through points on a line.

Through the following section I would like to broaden the focus of my discussion to the nature of borders. Or perhaps more specifically, to the ways in which borders are constructed and naturalized. To this end, I depart from Inge Boer’s (2006) work on boundaries7 in which she cites Diderot:

‘BOUNDS, ENDS, LIMITS. Terms that are all related to a finite expanse; the end marks up to where one can go; the limits, that which it is not permitted to cross; the bounds, that which it prevents from going forward. The end is a point; the limits form a line; the bounds an obstacle.’ (Diderot, 1751, II: 236; in Boer, 2006: 4).

This semantic elaboration can be transferred to a reading of the web-app that I have been concerned with. The points where individuals died (quite literally marked on the visualization) were their ends – the ends of their (life) journeys. In their conglomeration, these points form a line which marks a limit and this limit is at the same time an obstacle. From this perspective, bounds, ends and limits ‘prevent or hinder someone from what would otherwise be transgressed’ (Boer, 2006: 4); they inflict restrictions on human mobility, they close off possibilities. The ‘frontier’ can serve as an additional term to qualify the possible reasons for restrictions imposed by boundaries. The ‘frontier’ suggests an enemy on its outside.

These terms used to construct and denote boundaries are anonymous, in the sense that they do not prompt the question of who imposes the restrictions. Even in the case of a ‘frontier’ that evokes an opponent, the roles of human interactions tend to get erased in our approach to the term. Rather, Boer (2006) argues, they are perceived as ‘god-given’ or entities that have been assigned a truth value. Through her work, she aims to challenge this conventional approach to boundaries, which arises from the focus on what and where they are. Instead, she proposes that we probe the function rather than the definition of boundaries. This can allow us to understand boundaries as spaces in their own right – spaces in which events can happen – rather than as demarcating lines and to see beyond the material/ visible referent that boundaries are often taken to have. Through such an approach, more attention can be devoted to questions such as ‘who draws up the boundaries?’, ‘who takes them for granted?’ or ‘who is afraid they will be crossed?’ (Boer, 2006). I would like to argue that the former, non-function oriented approach to boundaries is also complicit in their naturalization, as it implies their truth.

In this light, the decision of the ISTR to document and visualize only the cases in which an individual could be said to have had the intention of crossing the border adds emphasis to this frontier. To borrow a term from Weber & Pickering (2011), these individuals can be seen as ‘illegalized travelers’. The visualization’s main concern can be understood as addressing the what (death/ killing) and where (Western border of Czechoslovakia) questions about this boundary; together these confirm the visual referent of the Iron Curtain. While questions about the function and space of the border zone were attended to in the research (Mašková & Ripka, 2015), these were excluded from the space of the visualization, making the frontier primarily stand out as an anonymous demarcating line.

The relationship between borders and death can be seen as a reciprocal one; as Weber and Pickering (2011) explain, deaths (at borders) can be seen as both outcomes of border policies and as justifications for border policies. Likewise, death understood as an end can be seen as evidence of a boundary met on a journey. This co-constructive relationship between the two leaves little room for doubt as to the existence/ nature of a boundary in a situation where both, policies and death, can be evidenced. One confirms the other; they are one another’s nature. If borders are seen as limits – lines – drawn by the state and deaths as ends – points – that can be marked on a map, the two can visually come to reinforce one another. Their superimposition as performed in the web-app draws these points out along a line; it is like presenting the solution to a connect-the-dots puzzle. Doubling down suggests a confirmation of an ontology – a border that was already there (either through death, or legislation, depending on your point of departure). In this sense, the border can be seen as a marker of a pre-existing division between the East and the West. This too implies a confirmation of the underlying dividing logic between an East-West binary.

A mechanism through which the performance of this dividing logic can be analysed is attentiveness. As Amoore (2009) explains, peoples’ lines of sight are directed through attention. Drawing on art historian Crary’s work, Amoore (2009) argues that contemporary uses of sensory stimuli can be understood as dividing practices, as means of isolation and separation (rather than simply ‘making a subject see’). Screened ways of ‘attending to the world’ have become dominant sites for sovereign decision-making in our society. It is at/through the screen interface that difference is both communicated and performed (Amoore, 2009). Through channeling attention to the points/line, the deaths/border, the screened ISTR web application can be seen as a performance of difference between East and West. By directing a viewer’s line of sight to the frontier between the spaces of Czechoslovakia and of Germany and Austria that persisted between 1948-1989, a dividing logic between East and West is being constructed. Although it may be argued that the division expired in 1989, it is the way in which this boundary is treated – as discussed above, non-functionally, as an anonymous truthful existence – that also comes to suggest a timelessness to the separation that is being made. Through its repeated performance that stems from sustained attention, a division can perhaps be said to be naturalized.

Boundaries in Maze Europe

In this final section, I dwell on the issue of naturalization a little more through making two brief comparisons to research engagements with borders in Europe. The first of these is a study by Havlick (2014) who analyses the Iron Curtain as a green belt across Europe based on experiences from a biking trip he did along the trail. He recounts that:

‘a journey along the Iron Curtain Trail can prove to be rather disorienting as there is no single story, no unifying narrative that pulls the disparate layers of this region easily into view. Instead, the traveler is pressed to consider the borderlands as complex socioecological landscapes. Even the borders themselves present a problem...’ (Havlick, 2014: 127).

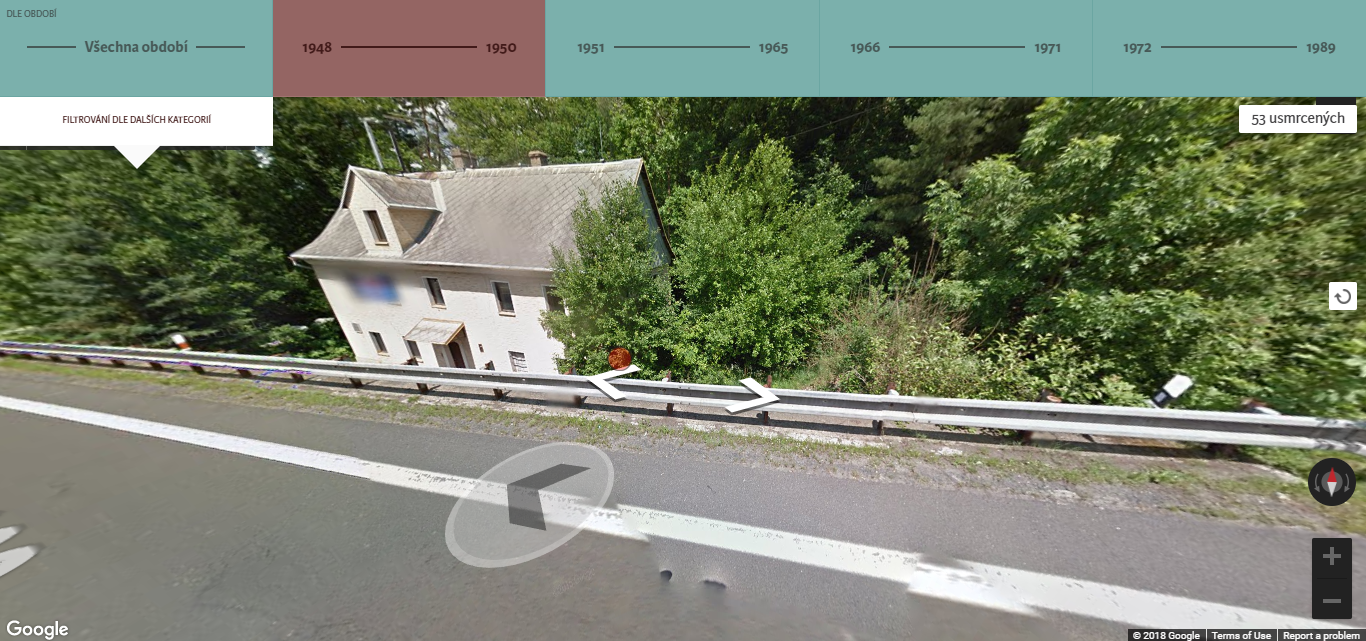

Through this account, the reader can perceive the border as a space in its own right. Its function can be questioned and focus moved away from the what/where questions that Boer (2006) criticizes. Havlick (2014) then goes on to explain that individual monuments commemorating the violence that had been imposed on people and place pulled him out of the landscape he was in. Conceptually, there is an interesting parallel to be drawn between Havlick’s experience and the experience one can have navigating through the ISTR web-app. The GoogleMaps API that it makes use of facilitates exploration of the space through StreetView. Navigating the border areas through StreetView, the experience is equally disorienting and non-linear as oppose to impression that one gets of the border from a 2D rendering of the map. It is primarily through the red points marking deaths in the space that I was reminded of the division that I was performing with the interface. Figure 7 shows one of these encounters, sometimes I could not find the markers in places the 2D map suggested they would be.

This comparison resonates well with Boer’s (2006) criticism of the way in which boundaries are often treated. In both cases, navigating the borders as spaces convolutes any lines that the space was previously reduced to; it is no longer a division between an inside and an outside. Hereby, the comparison further underlines my point; that attention dedicated to the points at which individuals were killed has the effect of performing and thereby naturalizing the division that they outline.

Through the second study that I bring in, I would like to situate this naturalization in the context of Europe and the EU. Christiansen and Jørgensen (2000) have proposed the metaphor of a ‘maze’ to conceptualize borders in Europe – a play on the notion of Fortress Europe. While the traditional image of a nation state conceives it as fully encircled by a boundary that separates the nation from the outside,8 such rigid boundaries have become blurred in today’s Europe. Christiansen and Jørgensen state that ‘the effect of borders in the new Europe is both to divide regulatory spaces and to create new ones which unite policy-makers from either side’ (2000: 62). This dual function of differentiation as well as unification is something that can be extended beyond the realm of governance. In accordance with Boer (2006), this focus on function also immediately opens the discussion up to a multiplicity of interpretations of the boundary – or at least to two. In the context of a maze, this dual function becomes permissible, perhaps even desirable.

The boundary sketched out by the Map of the Iron Curtain web-app is but a segment of a line; a traveler could easily go around this obstacle. It is no longer an impermeable Iron barrier as it would have been between 1948-1989, but it comes to constitute a border in the complex maze Europe. It marks a dividing line between (former) Eastern and Western Europe, a division that is simultaneously no longer imposed and existing. Although the two sides have been united, for instance by the physical removal of obstacles or the creation of a new boundary around the EU, the integration of Eastern Europe continues to be a concern of EU level policies, such as regional policy or memory politics. The web-app that I have been discussing here can be understood as a concrete visualization of just this. The images both undermine the border’s contemporary role and recreate it. Through participating in this dual function, the web-app acts in line with the types of borders that Christiansen and Jørgensen (2000) speak about. In doing so, they can be seen as naturalizing the divide/non-divide between East and West. With this example I also wish to underline the complexity of the matter; can it indeed be said that a border/non-border constructs rather than deconstructs divisions?

Conclusion

Borders enable the distinction between East and West. Although its placement may be arbitrary, a demarcating line is necessary for the diving logic between East and West to hold. The Map of the Iron Curtain web-app that I have discussed in this essay can be understood as an example of such a line. The GoogleMaps environment accommodates the selected cases in a familiar and legible space. The visualization transforms a selection of otherwise scattered, diverse physical documents into a seamless collective. It constructs the border through deaths, and, at the same time, deaths as a border. In doing so, the points construct the line while the line confirms the position of the points. Attention is directed to the whereabouts of these ends rather than to the function of the space that they inhabit. As such it can be argued that such a visualization serves to naturalize making divisions between East and West, as it gives limited attention to the in-between.

Notes

References

- Amoore, Louise. (2009). ‘Lines of sight: on the visualization of unknown futures’, Citizenship Studies, 13(1), pp.17-30.

- Bal, Mieke. (2002). “Introduction” & “Concept”. In Travelling Concepts in the Humanities: A Rough Guide. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp, 4-55.

- Boer, Inge. (2006). “Introduction”. In Bal, Mieke (ed); Van Eekelen, Bregje (ed); Spyer, Patricia (ed). Uncertain Territories: Boundaries in Cultural Analysis. Editions Rodopi BV.

- Christiansen, Thomas; Jørgensen, Knud Erik. (2000). ‘Transnational governance ‘above’ and ‘below’ the state: The changing nature of borders in the new Europe, Regional & Federal Studies’, 10(2), pp.62-77.

- Havlick, David G. (2014). ‘The Iron Curtain Trail’s Landscapes of Memory, Meaning, and Recovery’, Focus on Geography, 57(3), pp. 126-133.

- Law, John. (2015). ‘What's wrong with a one-world world?’, Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory, 16(1), pp. 126-139.

- Mapa.zelezna-opona.cz. (2015). Přes železnou oponu: Usmrcení na československé hranici. [online] Available at: https://mapa.zelezna-opona.cz/ [Accessed 8 Dec. 2018].

- Mašková, Tereza; Ripka, Vojtěch. (2015). Železná opona v Československu: Usmrcení na československých státních hranicích v letech 1948–1989. Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů.

- Peckham, Robert Shannan. (2003). “The Uncertain State of Islands: National Identity and the Discourse of Islands in Nineteenth-Century Britain and Greece”. Journal of Historical Geography, 29 (4), pp. 499-515.

- Pulec, Martin (2006). Organizace a činnost ozbrojených pohraničních složek, Seznamy osob usmrcených na státních hranicích 1945–1989, Prague: ÚDV.

- Ustrcr.cz. (n.d.). Dokumentace usmrcených na československých státních hranicích 1948−1989 - Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů. [online] Available at: https://www.ustrcr.cz/uvod/dokumentace-usmrcenych-statni-hranice/ [Accessed 19 Nov. 2018].

- Weber, Leane; Pickering, Sharon. (2011). Globalization and Borders: Death at the Global Frontier, Palgrave Macmillan.

Image sources

- Figure 1 : Own screenshot (Mapa.zelezna-opona.cz, 2015)

- Figure 2 : ‘Plánek místa trestného činu, 07.07.1980’ original document kept in the Archív Ústavu pamäti národa (Ustrcr.cz, n.d.).

- Figure 3: ‘Fotografické snímky k zastřelení J. Anděla z Frant. Lázní – hlídkou SNB u obce Kammerdorf, okres Cheb, dne 11. dubna 1948’ original document kept in the kept in the Archiv bezpečnostních složek (Ustrcr.cz, n.d.).

- Figure 4 : ‘Situační náčrtek místa použití zbraně strážm. Jiřím Lébrem SNB – útvaru Libá, okres Cheb, u osady Kammerdorf dne 11. 4. 1948’ original document kept in the kept in the Archiv bezpečnostních složek (Ustrcr.cz, n.d.).

- Figure 5 : ‘Orientační náčrtek místa použití zbraně strážm. Jiřím Lébrem příslušníkem SNB – útvaru Libá, okr. Cheb, dne 11. dubna 1948 (Zdroj: ABS)’ original document kept in the kept in the Archiv bezpečnostních složek (Ustrcr.cz, n.d.).

- Figure 6: Own screenshot (Mapa.zelezna-opona.cz, 2015)

- Figure 7: Own screenshot (Mapa.zelezna-opona.cz, 2015)